February 2023

VMAC Article

Expired Memory / Postmemory, Myra Chan

“The archive takes place at the place of originary and structural breakdown of the said memory” – Jacques Derrida

“Isn’t a memory something that has expired?” This question came to me when I discovered a VHS tape of Expired Memories in the VMAC archive. Memories invariably emerge from a lost past, so why label them as “expired”? Recently, this VHS tape crossed my mind again when I was reading Derrida’s Archive Fever.

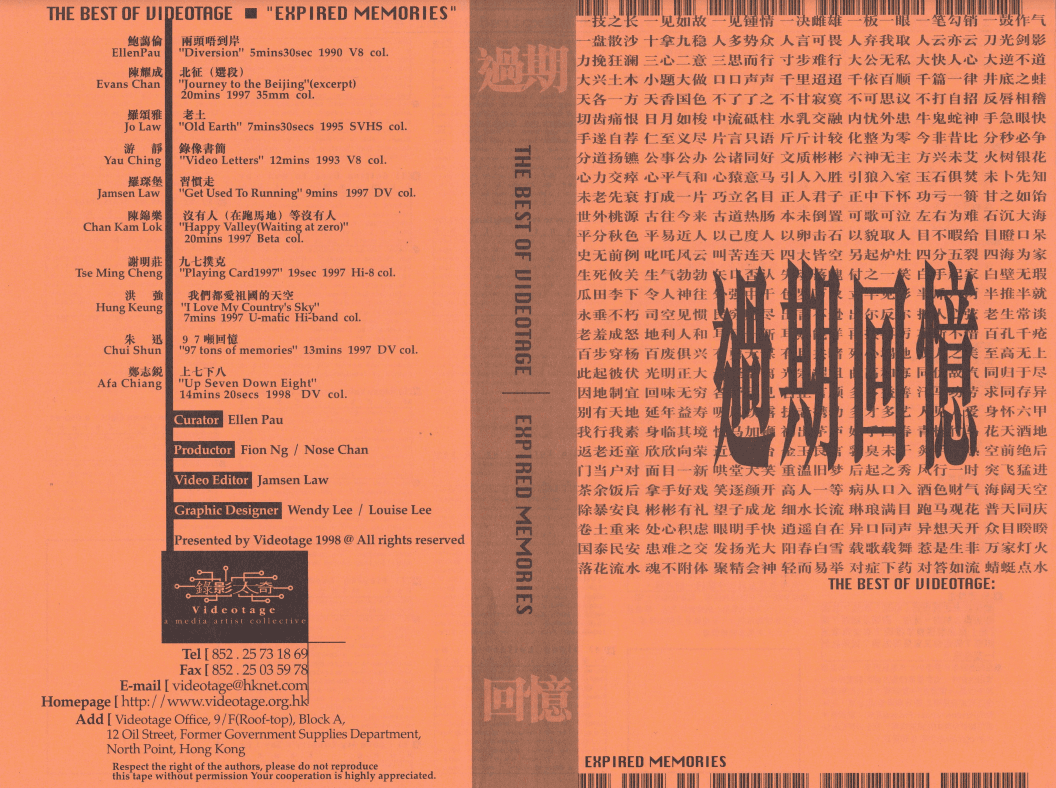

Between 1997 and 2001, Videotage published six volumes of The Best of Videotage. Each compilation presents a thematic selection of Hong Kong video art. Released in 1998, Expired Memories assembles the works by ten local artists in response to the handover of Hong Kong to China in 1997. [1] The historical significance of “expiration” is manifested in the compilation’s context. As 1 July 1997 marks the expiry date of British Hong Kong, the moving image works that capture diverse experiences and sentiments serve as artistic evidence of the epochal moment. From an archival perspective, however, what has “expired” concurrently points to the past and the future. It is not my intention to examine pre- and post-1997 video art or analyze the medium’s experiments and narrative forms deployed by early generations of Hong Kong video artists [2]; rather, I want to consider the archive’s expired memories and their relationship with history and postmemory.

The term “postmemory” was first introduced by Marianne Hirsch, a scholar of gender and memory studies, to describe the relationship of the second generation to powerful or traumatic experiences that preceded their birth but were transmitted to them deeply.[3] The “generation after” remembers never-experienced historical events by receiving knowledge from stories, images and behaviour during their growing up years. Through imaginative investment, projection, and creation reacting to fragmentary remnants of the past, a sense of “living connection” between the past and the present is established. Hirsch considers photography a potent medium of postmemory. Photographic images not only enable the viewers to see the bygone world but also remind them of the impossibility of retrieving what is lost. When the audience attempts to approach the historical past through documentation, it gives rise to desire projection and affective affiliation.

The indexical quality of photography and moving image allows them to be a privileged apparatus for representing reality as well as documenting histories. However, like other contemporary art forms, video art encapsulates in its expression ambiguous realities and sentiments rather than direct descriptions. The video works included in Expired Memories demonstrate varied screen practices, such as documentary filmmaking, diary film, video essay and found footage, mingled with traces of everyday and social events, private sentiments and collective memories. They document trivial, intimate and abstract experiences that are shaped by experimental visions. It would be futile if one looks for a concrete account of the history surrounding the 1997 handover from these artistic recollections.

Nevertheless, the development of Hong Kong video art is intertwined with that of the city’s socio-political environment. The (seemingly) expired experiences featured in the compilation provide alternative historical representations of 1990s Hong Kong while evoking connections with the postmemory of the second/future generation. For example, Evan Chan’s Journey to the Beijing (Excerpt) documents the “Walk to Beijing” in 1996 and includes interviews with people from all walks of life. The excerpt sheds light on the complex milieu in the 1990s that is characterized by heteroglossia, and it presents heterogeneous voices from individuals that lie outside of the grand narrative. Some of the other video are more oblique, while they are filled with traces and emotions relating to the 1997 handover. In Happy Valley (waiting at zero), a work that responds to the emigration wave of the period, Mark Chan repeatedly talks about ways of going to Happy Valley, and he keeps mumbling without saying anything concrete. In contrast to historical archives and mainstream cinema, the experimental narratives and convoluted storytelling in these works open up an expanded space for imagination and contemplation, calling forth the performative postmemory of the next generation.

An archive preserves all kinds of expired memories. As Derrida puts it, the desire to return to the lost origin and the possibility of forgetfulness drives the formation of archives. In other words, whether talking about the city’s history or art history, an archive seeks to address the finitude of the ghostly origin and to resist forgetting. As the public approaches the archive’s “expired” mediated experiences, the transmission-interpretation process generates spaces for imagination, transformation and deconstruction. If it is true that history exists in the “now-time” (Jetztzeit) as posited by Walter Benjamin, it brings forth an inevitable reflection on archives: How do expired memories made of fragments and ruptures overlap with our present and future?

Footnotes:

[1]. The selection of artworks includes: Ellen Pau’s Diversion, Evan Chan’s Journey to the Beijing (Excerpt), Yau Ching’s Video Letter 1-3, Jo Law’s Old Earth, Jamsen Law’s Get Used to Run, Chan Kam Lok’s Happy Valley (waiting at zero), Tse Ming Cheng’s Playing Card 1997, Hung Keung’s I Love My Country’s Sky, Chu Shun’s 97 Tons of Memories, and Afa Chang’s Up Seven Down Eight: A Chorus.

[2]. For related articles, see Lai, Chiu-han Linda, “Documenting Sentiments in Video Diaries around 1997: Archeology of Forgotten Screen Practices” (2015) and Leung, Isaac, “The Resilient City: When Social Activism Meets Media Arts in Hong Kong” (2020).

[3]. See Hirsch, Marianne. The Generation of Postmemory: Writing and Visual Culture after the Holocaust. Columbia University Press, 2012. In the book, Hirsch discusses the workings of trauma, memory and intergenerational transmission within the historical context of the Holocaust.

(The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author/s. They do not necessarily represent the views of VMAC.)

VMAC New Collection

Image: Yves Etienne Sonolet, Molting Cities-O Sole Mio, (2014)

In 2022, VMAC is honoured to invite Macac-based artist-curator Bianca Lei to be the guest curator of the Macau Collection, which brings together a total of seven artists and 16 artworks. The series showcases Macau’s history and development, and the emotion of the body reflected in the city in artworks spanning animation, documentary, performance art, experimental video and slow cinema. The artists record, reflect on, and critique their surroundings through creative acts in an ever-changing society.

Macau Collection:

- Jose Drummond: Painter (2005); The Skeptic (2008), The Pretender (3 of 11 letters) (2001)

- Nosh Ng: Ferriage I (2009)

- Alice Ng: From Something to Naught (2002-2008); Nothing Happens – Macao series (1-5) (2014); The Waiting Room – Nothing Happens (2014)

- Ho Ka Cheng: Colour Bar Test Pattern (2008)

- Yves Etienne Sonolet: What Makes the Boat Float (2013); Molting Cities-O Sole Mio, (2014); Abstract for “Dialogues Among Multiple Dimensions” (2018)

- Zhu Biyi: Move 2.1& 2.2 (2011); Vent-Hole (2014)

- Bianca Lei: The Scars of my City (Chapter 1-7) & (Chapter 8) (2011, 2015); Drawing the urban space–negative space (2012); Faith in Fake ix – The shadow said: “…” (2018)

Staff Pick (In Chinese only)

About VMAC Newsletter

VMAC, Videotage’s collection of video and media arts, is a witness to the development of video and media culture in Hong Kong over the past 35 years. Featuring artists from varied backgrounds, VMAC covers diverse genres including shorts, video essays, experimental films and animations. VMAC Newsletter, published on a bi-monthly basis, provides an up-to-date conversation on media arts and their preservation while highlighting the collection and its contextual materials.