February 2024

VMAC Article

Gaming, Horror, and New Narratives: Who’s Lila?

Text: Lewa Chan

In 2022, a global lockdown left everyone wrestling with anxiety and fear in the confines of their homes. Undeterred, talented young creators made VHS-inspired retro horror video works and video games as a response to the unspeakable fears of reality, producing eclectic works known as “Analog Horror”. As a follow-up to my presentation at VMAC Forum – Analog Horror: Revival of Creepypasta as Community-Based Video Artertainment, I would like to introduce an experimental Analog Horror game that explores narrative, philosophy, and propagation.

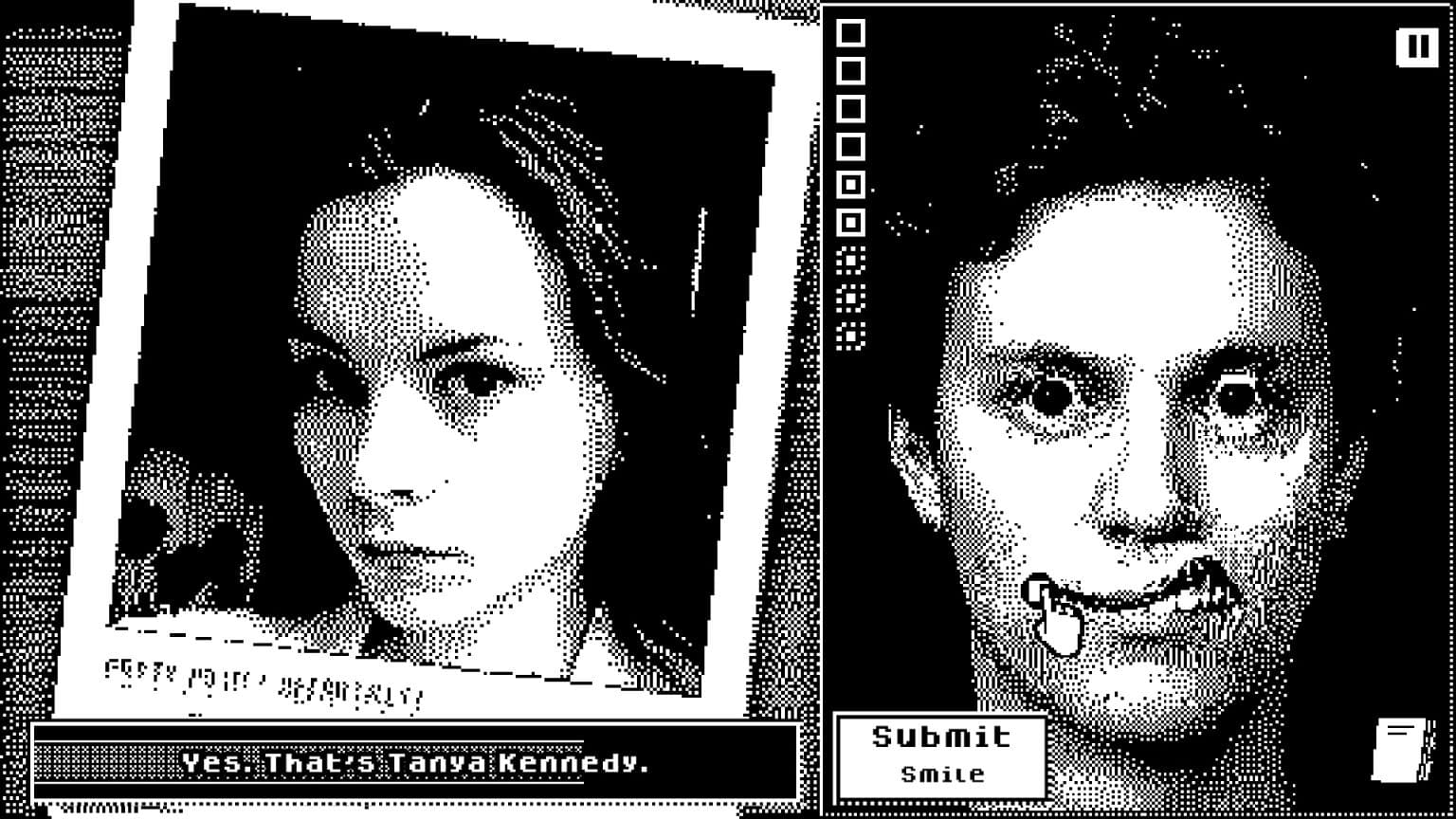

Who’s Lila? is a 2022 point-and-click adventure by Russian indie game-maker Garage Heathen. In a similar vein as Return of the Obra Dinn (2018), Who’s Lila? uses low-pixel, monochrome, 3D visuals that resemble PS1- and Gameboy-era video games, bringing back the lost art of uncertainty to the hyper-realistic modern gaming world. Clicking “Wake Up” in the menu begins the journey of Will, a high school student who struggles to express his feelings and practises facial expressions every day in front of a mirror. As Will arrives at school, his classmates whisper about him. Soon we learn that Tanya, Will’s classmate, has been missing for days since the last school party and that Will was her last contact. The player controls Will’s actions and facial expressions in a quest to learn about him, Tanya, and the mysterious “Lila”, and to unearth the truth behind a series of entangled events.

Who’s Lila? is a unique interpretation of the form and narrative of video games, as well as of fiction itself. In most video games, what the protagonist sees is what the player sees. Secondary information, such as items and health, appear in the corners of the screen; facial expressions of the player’s character are rarely displayed (sorry DOOM fans). It is an example of visual hierarchy in game design that immerses the player in the character’s world. Who’s Lila? breaks this convention by displaying Will’s face over almost half of the screen. When deciding on facial expressions for Will, the player is sometimes countered by Will’s muscles (or consciousness?). Being “low-poly”, the game makes it difficult for the player to figure out how each character looks, as their faces seem to shift along their bodies. The game design seeks to constantly evoke a sense of unease and detachment for the player.

Who’s Lila? uses non-linear storytelling and gameplay. The game consists of 15 endings, each of which starts with the player “waking up” as Will and looking for clues to who Lila is within fragmented, surrealist dioramas of interrelated yet paradoxical events. In some story lines, the game requires players to solve puzzles outside of the game’s environment, such as using X (formerly known as Twitter), word editing software, or add-on (plugin) to obtain information needed to advance the plot. As the game progresses, conversations between characters become conversations between the characters and the player in Will’s body. While breaking the fourth wall is nothing new, Who’s Lila? explores the possibility of Tulpas/Thought-Forms in the Internet age, as well as propositions about creativity, consciousness, and metaphysics, bringing forth an in-depth discussion rarely seen in mainstream video games.

Heavily influenced by David Lynch, Who’s Lila is a fascinating work for fans of psychological horror and film d’auteur. From character design (Will looks a bit like Dale Cooper, no?), nightmarish scenes, stream-of-consciousness dialogue, to the subject of Tulpas/Thought-Forms, Who’s Lila? is one of the few works that directly reference and show thorough understanding of Lynch’s work and intentions, as it sheds a new light on established subjects while demonstrating artistic value in its own right.

Times have changed. After 30 years of being cast as youth-poisoning and marginal entertainment, video games are now an unique medium of cultural values that is inseparable from the world we live in. Video games can be a new tool for media artists to express their ideas, i.e. “Game Art” (as discussed in a recent VMAC Forum), or an interactive vessel for art-conscious game enthusiasts to showcase their talent and turn entertainment into an artistic experience, i.e. “Art Game”, as in “Art Pop” and “Art Film”.

It is no exaggeration to say that Who’s Lila? is an art game, but that leads us into another rabbit hole: Video game directors such as Hideo Kojima, whose work incorporates artistic elements of film or other media, is (self-)conscious about the subject of video games, fandom, and the real world, while it displays a certain artistic values. But can video games be considered art? Or are they simply a form of entertainment that is “artistic”? This brings us back to the question of the modernist era: “What is art?”

(The views and opinions expressed in this article published are those of the author/s. They do not necessarily represent the views of VMAC.)

Programme Archive

“VMAC Forum – WASD- Video Games as Alternative Narratives” is now available on YouTube (in Cantonese only)

Click to Watch

In December of last year , VMAC Forum hosted a talk by two media artists, Hui Wai-keung and Yip Yuk-yiu, who shared their experiences and ideas about game art.

Both artists used different hacking techniques to transform the narratives or gameplay modes within games. Hui Wai-keung presented three of his works that utilize video games as a medium. In his earlier works, he manipulates characters into performing unconventional actions, highlighting the communal nature of multiplayer online games through interactions between himself and other players. His later works integrate re-enactment, as well as the philosophies of Aristotle and Nietzsche, prompting reflections on game narratives, history, and culture. Yip Yuk-yiu, on the other hand, spoke of several works that inspired his creations. He analyzed how these works use hacking techniques to break existing frameworks and convey thought-provoking messages. Through exploration of virtual worlds, Yip’s works employ documentary-style approaches, appropriation, and new media to document a world constructed by contemporary cultural artifacts, which also becomes a personal record of the artist’s life.

At the forum, both artists showcased their unique perspectives on and creative approaches to game art, offering the audience a fresh viewpoint on game art.

Staff Pick

Artspace Newsletter, 1997

In the May 2022 issue of the VMAC Newsletter, Phoebe Wong’s article ‘Archiving the Video Circle‘ discusses the disparity between documentation, particularly the lack of photographic documentation, and the prominence of the video installation work Video Circle. Recently, VMAC has unearthed other documentation of the work, including a newsletter from Artspace, an artist-run gallery in Australia. In 1997, Ellen Pau, who was on an artist-in-residence programme at Artspace, presented Video Circle 1 and 2 to Australian audiences.

About VMAC Newsletter

VMAC, Videotage’s collection of video and media arts, is a witness to the development of video and media culture in Hong Kong over the past 35 years. Featuring artists from varied backgrounds, VMAC covers diverse genres including shorts, video essays, experimental films and animations. VMAC Newsletter, published on a bi-monthly basis, provides an up-to-date conversation on media arts and their preservation while highlighting the collection and its contextual materials.